One night at a club many years ago, I met someone who told me he was appearing in a big play. More specifically, he said he was in Six Degrees of Separation. It was true or a lie, depending on your point of view. New York Magazine later reported that David Hampton, the man whose life inspired Six Degrees of Separation, was going around, telling people that he was “in” the show. To an extent, he was all over John Guare’s famous play. And from another point of view, the claim that he was in the show was fiction – something in which David Hampton, like John Guare, specialized.

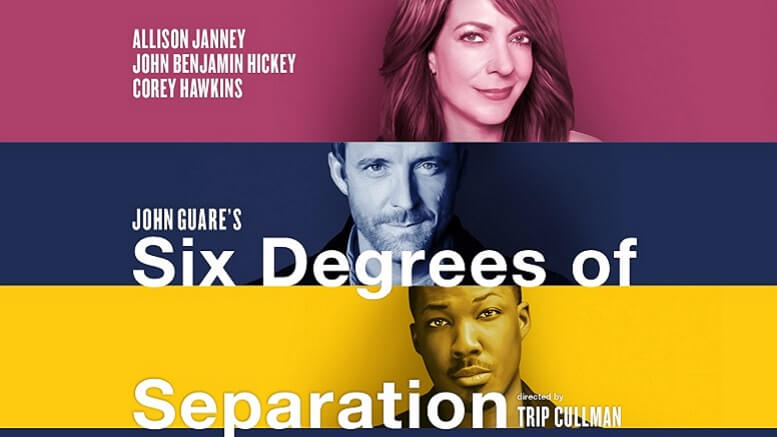

The thousands of people streaming in to see John Guare’s play on Broadway these days may enjoy the show, the acting, the writing and the production. Some may even know that it was inspired by the true story of David Hampton. But it’s unlikely they know much about Hampton’s life beyond the way it’s been adapted and altered for the play – and what happened after the show debuted. The Broadway revival may make it appropriate to look back at Hampton as well as to Guare.

One is a playwright able to transform experience into entertainment. The other was someone who reinvented himself again and again, often with tragic consequences, a fraudster, a fabulist or even an actor who used the world as his stage, creating characters that, in the end, were cons. One penned Six Degrees of Separation. The other inspired the show, but lived a life more aptly titled Six Degrees of Incarceration. Hampton tried hard to benefit from the story he had created, but never succeeded, creating new characters and cons long after the play debuted. One’s reward was income and recognition, while the other’s was incarceration and a steady stream of efforts to reinvent himself through new roles in life.

”He would often call me for advice,” Ronald Kuby, a lawyer who represented Hampton when Guare sued him for harassment, told The New York Times. ”All I could tell him was to stop doing these things.”

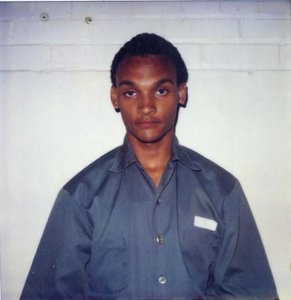

DAVID HAMPTON fascinated people with his stories and inspired a Broadway play, but never reaped the rewards.

David Hampton was born in Buffalo on April 28, 1964 and died at age 39 on July 18, 2003. He came to New York, hoping to make it big.

“David Hampton arrived in New York City in 1981 set on pursuing an acting and dancing career,” according to one obituary.

Hampton, who had studied acting at SUNY Buffalo (when he showed up to class: He wasn’t always there), ran into tough times in New York City. He soon discovered his biggest roles would be on the street, not on stage. It turns out he got the idea to play “David Poitier,” Sidney Poitier’s fictional son, outside a night club. When he and a friend couldn’t get into Studio 54, they decided to pretend to be celebrities. Why not? It seemed like an innocuous enough way to get into the exclusive club. His friend became Gregory Peck’s son and Hampton became Poitier’s son. It not only worked. It worked perfectly. David Poitier was a celebrity, ushered in with respect. Hampton decided that being David Poitier had fringe benefits. He left Studio 54, but he didn’t leave David Poitier behind. His alter ego, his more famous half, was born. But what could he do with it?

This is where the con went from a clever game to fraud. Hampton stole an address book that belonged to Robert Stammers, a student who had attended Andover. He called the parents of people in the book. The response was refreshing. Whether gullible or eager, they became the audience for his upcoming performances. They were enchanted by the idea of meeting Poitier’s son, welcoming him into their lives. Hampton found that even celebrities were eager to meet, greet and help him or at least the person he purported to be. People were nice to him. They treated him well. Hampton didn’t just get into a night club. He got into an exclusive world. David Poitier could get into nearly any door.

Studio 54 was nothing compared to the people who ushered him into their lives, if only briefly. Gary Sinise and Osborn Elliott, the dean of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism and former Newsweek editor, helped David Poitier. Hampton told stories about the star and even suggested that he might be able to snag roles for his benefactors. Would they have helped David Hampton? It’s possible, but there’s no way of knowing. Hampton, however, had found celebrity was the key that opened doors. He wasn’t asking favors of celebrities: He had become one of them. White people whether out of kindness or prejudice or some other motive were eager to help Hampton’s alter ego. This was a more naïve time before “fake news” became so common.

People at once enjoyed meeting and, it seemed, took pity on Sidney Poitier’s son. Hampton fooled people into thinking he had missed a plane, lost his luggage or been robbed. On the one hand, he was a con artist. On the other, he could be seen as an out of work actor a little bit along the lines of Tootsie. Hampton created a character, acting his way into the lives of the affluent – sometimes similar to those filling the audience of the show today. And he didn’t always succeed. He tried and failed to fake his way into Andy Warhol’s circle. Hampton explained his inability to con Andy Warhol very simply.

“Andy was a con artist himself,” Hampton reportedly said. “One salesman can always spot another.”

Hampton tended to wear out his welcome, sometimes startling his hosts. Inger McCabe Elliott and Osborn Elliott (AKA Oz) walked in on “David Poitier” in bed with another man in their home. Hampton said he was with Malcolm Forbes’ nephew, who had been locked out of his apartment. Now the lies had gone too far. He and Malcolm Forbes’ nephew were unceremoniously shown the door. Hampton asked if he could borrow money – to send his hosts flowers, thanking them for their generosity. While this all may have seemed like an exercise in fantasy, it also was a case of fraud. If you need to borrow money, the legal way, then you could check out Lending Expert for further details on how you can secure a loan.

Hampton’s house of cards came tumbling down when he was arrested and convicted of fraud in 1983 and sentenced to 18 months to four years in prison. Not a happy ending for Hampton or David Poitier, if it was an ending at all. But just as David Hampton had been reborn in the roles he created, he was about to be reincarnated in possibly the most successful way. Guare heard about Hampton’s escapades from the Elliotts, who had gone from being enchanted to embarrassed. He then read the news accounts and wrote Six Degrees of Separation, which opened at Lincoln Center, and became a hit. Hampton watched all of this from the sidelines, trying to capitalize on the Six Degrees of Separation’s success.

“You don’t take someone’s life story without contacting them,” Hampton told New York Magazine. “You don’t do that.”

Of course, he had “stolen” lives or identities and been punished. How could someone else now steal his life and be rewarded? Hampton did his best to benefit once he saw his life all over, if altered, in Guare’s play. Although Paul in the play becomes violent and threatening, Hampton always insisted he never did that. He gave interviews, crashed parties and threatened Guare. He even posed as the author of the play, telling NYU students that he had written the show. Hampton showed them an article about the show with his picture, because the play was based on him. He didn’t let them read the actual article. Hampton even filed a $100 million lawsuit, arguing that Guare had stolen his story.

You might think, on the surface, Hampton had a good argument. Guare clearly based the story on Hampton’s activities. And Hampton in the case contended that he was now the victim, not of a con, but of a work of art that had expropriated his life. What’s more precious than one’s identity? His, he argued, had been stolen. That was “him” on stage. While the playwright had based the play on Hampton, the suit never went anywhere. Studios pay people for the rights to their story all the time. Guare hadn’t paid Hampton. Still, there was a problem. Other suits charging that works of art stole someone’s story had failed, since the artists argued they used it as a starting point for fiction. Hampton’s story also had appeared in numerous media accounts and been fictionalized. And he had committed a crime, which didn’t help. So yes, David Hampton was in the play or at least he was reincarnated as a character. But he only ended up incarcerated, not obtaining income, for his role.

Hampton argued he had the right to benefit from “the fruits of his labour.” The judge saw it differently, saying “society’s response to one whose labours are in violation of its penal laws is punishment, not reward.” The biggest penalty wasn’t time in jail, but the inability to reap income from work that his life had inspired. Guare did not compensate Hampton, but argued the con man was harassing him. Hampon wasn’t convicted of harassment, but could hardly be said to be a winner in this scenario where the plot continued long after the play opened. While Guare’s play went on to have a life of its own, Hampton continued to live through characters he invented. He took on various identities, going in and out of jail.

Hampton even tried to get roles, saying he was appearing in Six Degrees of Separation. He instead kept playing characters on the street, improvising his way through life. Hampton appeared on TV in a show called The Justice Files as a con artist rather than an actor who had taken Shakespeare’s phrase that “all the world’s a stage” very literally. While David Poitier may have disappeared due to the notoriety of that fictional figure in the play, Hampton brought various other characters to life in his performances. He traveled to Seattle, where he introduced himself as Antonio de Montilio, the son of a wealthy physician. Hampton claimed to have been mugged on his way to interview Bill Gates for Vogue. He always presented himself as the victim. It frequently worked, at least for a while.

In the end, Hampton reduced the distance between himself and Guare’s success to one degree of separation, but that wasn’t enough to help him. It was a degree that was difficult to bridge. He argued he was taken advantage of, because his life inspired a show that never produced any income for him. And to an extent, he may be right. His most precious possession, his life story, never earned him the money that he hoped. He returned to New York City, where he died in Beth Israel Hospital of AIDS-related complications. He never made a penny from the play and struggled all his life, creating character after character. He took on the aliases Patrick Owens and Antonio Jones, although he contended he was engaging in fantasy not fraud.

“I never beat anyone over the head,” Hampton once said. “I was a perfect gentleman.”

In a strange way, it’s possible to argue that David Hampton became the biggest victim of his cons. He did entertain people, until they found out the truth. He never wrote his own life story, never put it all down on paper the way John Guare did, although in altered form. While Hampton inspired John Guare’s most famous play, he never benefited in any way, unless you call notoriety a reward. He did, however, create some great roles on and off stage. One could argue that Paul, on Broadway, is one of them even if John Guare transformed the character from one on the street to one in a show.

Find a part for yourself in Show Business today. Membership is FREE! CLICK HERE